Dridex Trojan

Dridex in a Nutshell

Dridex is a famous banking Trojan which appeared around 2011 and is still very active today. This is because of its evolution and its complex architecture, which is based on proxy layers to hide the main command and control servers (C&C). The APT known as TA505 is associated to Dridex, as well as with other malwares such as TrickBot and Locky ransomware. Dridex is known for its unique anti-analysis techniques which combines API hashing with VEH (Vectored Exception Handling) manipulation. As a consequence, Dridex is able to effectively hide its intentions and requires skillful reverse engineers to accurately dissect it. Once installed, Dridex can download additional files to provide more functionality to the Trojan.

Technical Summary

- Dridex uses API hashing to conceal its imports. It’s using CRC32 hashing, as well as another layer of XORing with hard-coded key. It’s prasing the loaded DLLs in memory and its export tables. As a consequence, Dridex can resolve any imported win APIs then jumps to their addresses.

- Another layer of complication is done with Vectored Exception Handling manipulation. Dridex inserts a lot of

int 3andretinstructions everywhere to make the reverse engineering harder. Furthermore, the use ofint 3triggers a custom exception handler planted by the malware. This malicious handler alters the execution flow to effectively jump between APIs. - Dridex comes with encrypted strings on its

.rdatasection. These strings are used as API parameters/settings for the malicious impact. Therefore, they are must be decrypted to know its intentions. Dridex uses RC4 to do the decryption. The first 40 bytes of every data chunk is the key (stored in a reverse order) then followed by the encrypted data. - Dridex stores its network configuration in plain text on its

.datasection. Obviously, it establishes connection with its C&C for further commands, and also to download additional malware modules. These modules extend its functionality. Dridex comes with 4 embedded C&C IP addresses.

Technical Analysis

Defeating Anti-Analysis

API Hashing

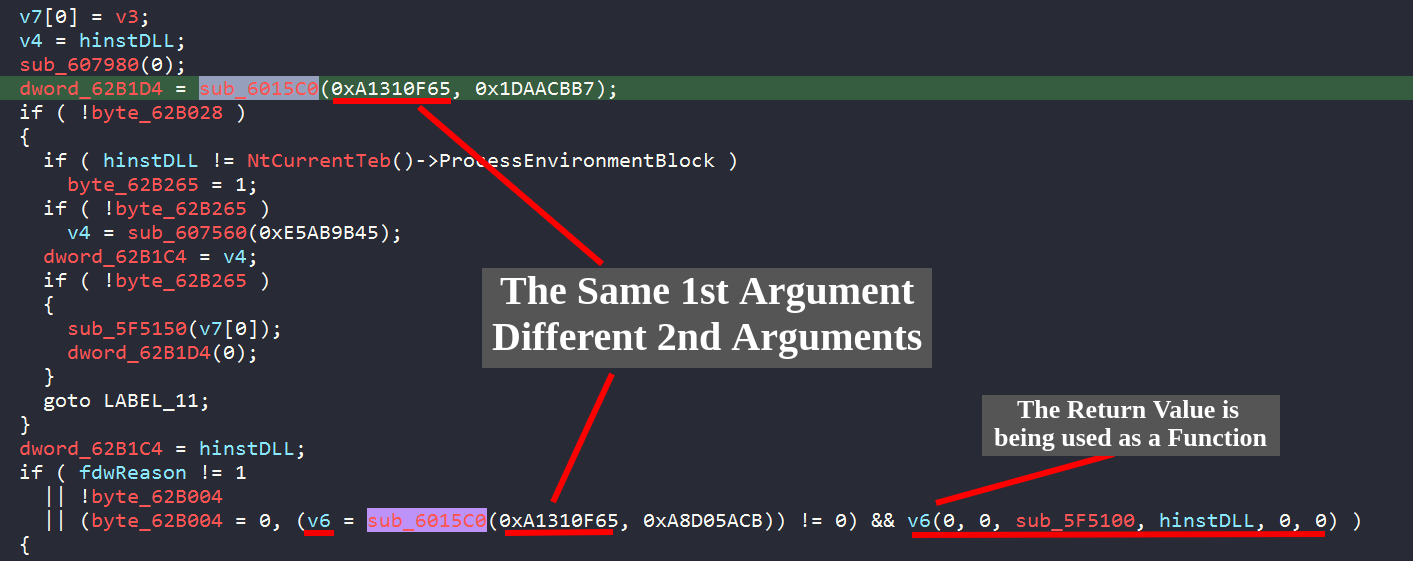

Dridex is famous for its anti-analysis techniques which include API hashing. API hashing -in a nutshell- is when a malware hashes the names (strings) of its imports, making it harder to know what APIs it will resolve at run-time. API hashing is famous among shellcodes. That’s because a tightly crafted shellcode can’t make use of the OS loader, it’s not a PE file and it must depend on itself to find where DLLs are residing in memory. Once it finds the targeted module, it parses its export table to know where it’s providing its exported APIs (the address in memory). One way to spot API hashing techniques, is to look for a function which takes constant (random-like data) inputs, and finding that they are using its return value as a function pointer.

We can see that sub_6015C0 matches the description we have just stated. It’s called twice to resolve two Windows APIs. Also, we can notice that the 1st parameter is the same during the two calls here. This may indicate that the 1st parameter is likely to be the hashed DLL name and the 2nd parameter is likely to be the hashed API name.

We can label sub_6015C0 as a potential API resolving routine. Now let’s dive into it for more detailed analysis.

We can see that it’s depending on two more functions: sub_607564 and sub_6067C8.

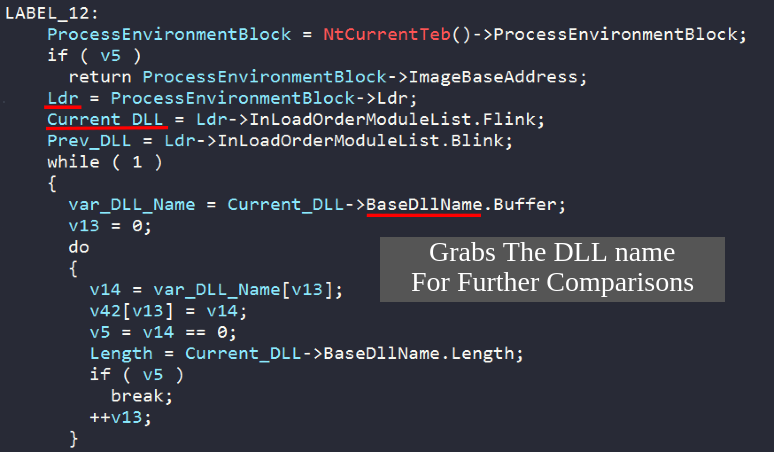

In sub_607564, we find that Dridex is parsing the process PEB structure in order to get the loaded modules- in the process address space-. By using the appropriate structs in IDA Pro, the code looks more readable right now.

| Variable Name | Struct |

|---|---|

| Ldr | Pointer to _PEB_LDR_DATA |

| Current_DLL | Pointer to _LDR_MODULE (Click the link and search the documentation) |

| Prev_DLL | Pointer to _LDR_MODULE |

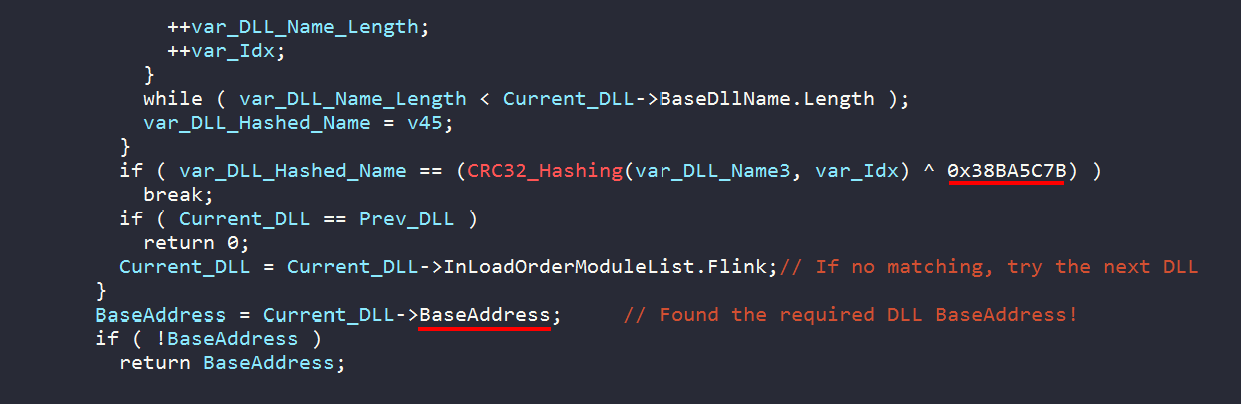

As we can see, Dridex is using the Flink pointer to parse the loaded modules (DLLs) as _LDR_MODULE structs. The BaseDllName of every loaded module is obtained, and properly converted to the right form for further comparison. The BaseDllName is hashed by sub_61D620 and XORed against the 38BA5C7B hard-coded key.

We can determine the type of hashing algorithm using PEiD tool. Using the Krypto ANALyzer plugin, it was able to identify the hashing algorithm as CRC32 based on the used algorithm constants. After hashing and XORing the BaseDllName of the loaded module, it’s compared against the target hash. Once there is a match, at 0X60769A, the BaseAddress of the wanted module (DLL) is returned. This address is used later for locating the wanted API within the module’s export table. This address also points to the IMAGE_DOS_HEADER aka MZ header of the module. All that is purely done in the memory without the need of exposing the malware’s imports.

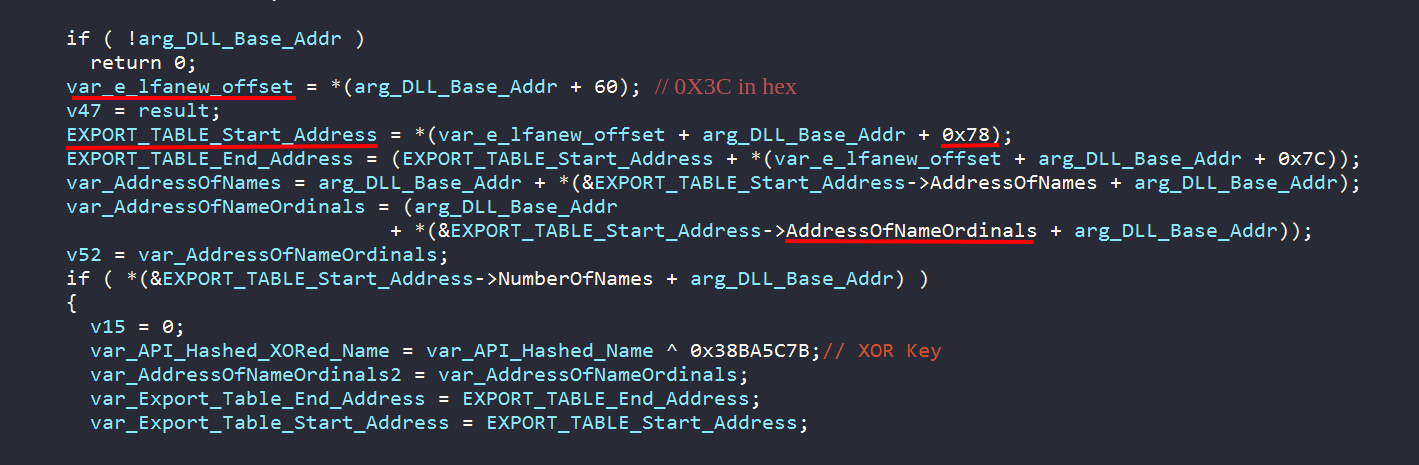

We proceed to reverse sub_6067C8. The routine accepts the previously returned DLL BaseAddress as a parameter along with the second hash. We can make a strong prediction that this function is using those parameters to return the API address in order to be used by Dridex. As we can see, The malware is parsing the module header in order to locate its export table. The export table of a certain DLL contains the addresses which its exported APIs are residing in memory.

The malwares first references the e_lfanew field at offset 0X3C from the beginning of the module. This field denotes the offset which the NT Headers begin. From there and by offset 0X78 -i.e. at offset 0X3C + 0X78 = 0X160 from the beginning of the DLL-, the malware can access the Data Directory. The first two fields of this array is the address of the Export Directory address and its size. We can use PEBear tool to visualize all these offsets within the PE header. We use the _IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY struct with the variable EXPORT_TABLE_Start_Address to make the code more readable.

Hence, we can see the malware parsing AddressOfNames, AddressOfNameOrdinals, and AddressOfFunctions to make a mapping between every exported API’s name and its memory address. If the hashed -and XORed- API name matches the 2nd argument of the function, its memory address is returned. By using this way, Dridex is able to effectively hide its needed APIs from security solutions. For more details about how to find an API address in memory check this out.

Combining all together from the previous analysis, we now know that Dridex is doing API hashing using CRC32 + another layer of XORing. We can try to write a script to create a hash table of the famous Windows DLLs and their exports. Generating this table, we can then search into it using the hashes that Dridex uses. As a consequence, we can know which API and DLL Dridex is trying to resolve without the need of dynamic code analysis.

Fortunately, we don’t have to create this script. We can use the amazing hashdb IDA plugin from OALabs. It will automate everything for us. We just need to identify the hashing algorithm and the XOR key to make hashdb ready.

This announces our victory over API hashing anti-analysis, and we can easily use the newly added enums to make the malware code more readable right now. For instance, at 0X5F9E47 we find that CreatThread is being resolved at that particular address.

Vectored Exception Handling

To fully understand the intention of this anti-analysis technique, we need to know how Dridex is utilizing API hashing:

The returned API address from sub_6015C0 (labeled as mw_API_Resolver) is not used as call instruction operand. Rather, at sub_607980, Dridex is registering (adding) a new customized Exception Handler using RtlAddVectoredExceptionHandler API, which accepts an _EXCEPTION_POINTERS arguemnt. This customized exception handler will adjust the thread stack and EIP register, in order to alter the process flow to the previously resolved API address (via the ret instruction).

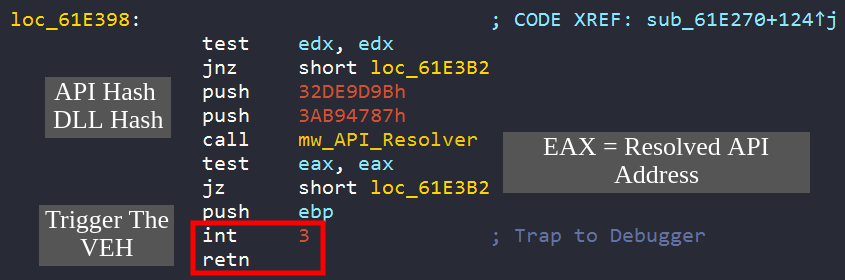

After calling the mw_API_Resolver function, EAX now contains the address of the resolved API. Dridex then traps the debugger or -more accurately- generates an EXCEPTION_BREAKPOINT using int 3 instruction. This exception is passed to the process exception handlers vector in order to be properly handled. The previously planted customized exception handler will be the first to process the exception.

This malicious handler will execute and alter the process’ context if and only if the exception is caused by int 3 instruction -which Dridex exactly wants-. The final process’ context will be altered by these steps:

-

Incrementing

EIPby 1 in order to make it point to theretinstruction. -

Mimicking a

push EIP+1instruction, in order to save the address of the instruction afterreton the stack ( manually building a stack frame). -

Also mimicking a

push EAXinstruction, in order to makeESP = Resolved API Address.

Successfully achieving these steps, the flow will exactly resume at the ret instruction, pointed by the corrupted EIP, which will pop the address on top of the stack and jumps to it. This will make the wanted jump to the resolved API with no call instruction. Furthermore, after executing the resolved API code, the flow resumes at the previously saved address of the manually built stack frame (step no. 2). This will make the flow resume at the instruction after the ret, successfully returning back to the previous normal flow before the int 3 instruction. Not to forget, this technique makes the dynamic code analysis harder, because you will deal with hundreds of debugger traps everywhere in the code.

Moreover, inserting ret instructions everywhere in the code tricks the disassemblers when trying to identify functions. Some disassemblers use ret instructions to identify the end of the functions. This makes another layer of complication using this anti-disassembly technique.

To overcome all this, we need to create a script which parses the code section of the sample, in order to fix those complication.

We can create a small IDA Python script to search for the opcodes int 3 and ret, and then patch them to be call EAX . This means that we are looking for the bytes 0xCCC3, then we patch them to be 0xFFD0. The script is below:

import idautils

import idaapi

import ida_search

def get_text_section ():

for seg in idautils.Segments():

if idc.get_segm_name(seg) == ".text":

return [idc.get_segm_start(seg), idc.get_segm_end(seg)]

def search_N_patch(pattern, patch):

search_range = []

search_range = get_text_section()

flag = True

while(flag): # The value 16 is the default.

addr = ida_search.find_binary(search_range[0], search_range[1], pattern, 16, ida_search.SEARCH_DOWN)

idc.patch_word(addr,patch)

if (addr == ida_idaapi.BADADDR or addr >= search_range[1]):

flag = False

pattern = 'cc c3' # int 3 ret

patch = 0xd0ff # call eax (Little Endian)

search_N_patch(pattern,patch)

PS: This script only alters the IDA database and not the actual binary. To patch the sample in order to open it in a debugger, use the pefile python library instead.

Now, using hashdb as well as our IDA Python script, we have a better chance to understand Dridex functionality. First, we edit the data types of the mw_API_Resolver arguments to be hashdb_strings_crc32 enum instead of integers. This in order to make IDA Pro automatically resolve the hashes, Secondly, we use IDA Pro Xrefs to know which API is being resolved at any particular location.

Strings Decryption

Dridex contains a lot of malicious functionality. From simple host profiling up to DLL hijacking, there are a lot to cover when reversing Dridex. I will not dive deeply into all of its functionality, I will rather focus on the interesting parts only. To get the most of its intentions, you need to decrypt all the embedded strings. They are stored on the .rdata section in chunks. These strings are used as parameters with the resolved APIs to perform certain malicious impact.

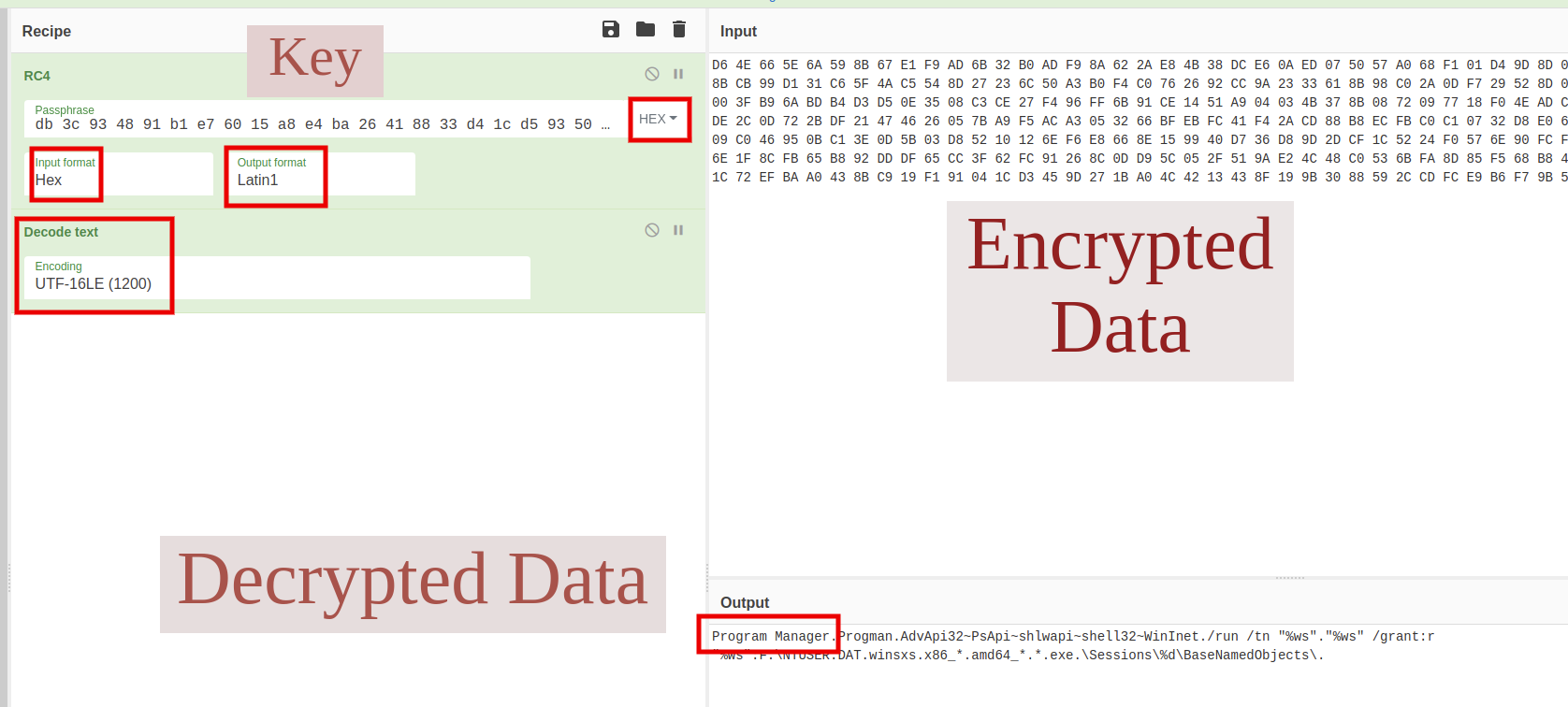

We can use the amazing capa tool from Mandiant to find out if it can detect any encryption algorithms. Fortunately, capa was able to identify RC4 is being used at sub_61E5D0. Also, from capa’s output, we can detect the operation: “key modulo its length” at the address 0x61E657.

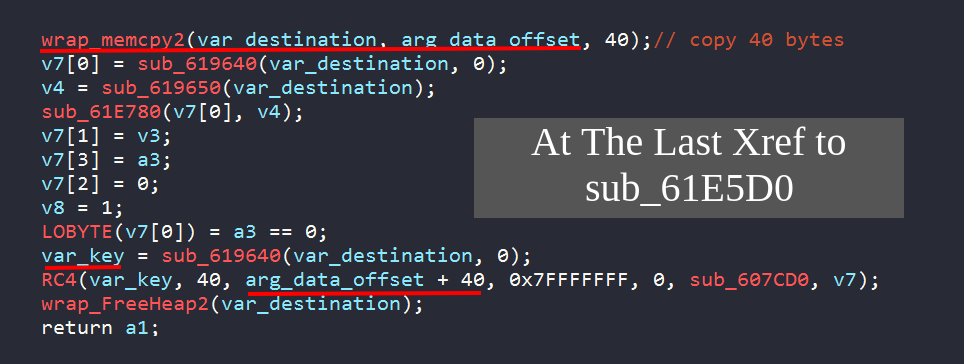

From here, we can trace the Xrefs to sub_61E5D0 to find out where the key is located and what is the key length. Taking the last Xref, at sub_607B30, we can trace back the function arguments to find that the key is loaded from a certain offset at the .rdata section. The key length is 40 bytes and the data to decrypted starts after the key. As a consequence, we can deduce that for every chunk of data, their decryption key is the first 40 bytes then followed by the encrypted data. Also from other threat intel resources, we can know that Dridex stores the decryption key bytes in a reverse order.

Let’s try to use CyberChef to manually decrypt the data at the address 0X629BC0. The key starts at 0X629BC0 with a length of 40 bytes in a reverse order. The encrypted data starts at 0X629BE8. We can see the fully decrypted strings clearly now. The first two words are “Program Manager”. That’s why I didn’t prefer to reverse all of Dridex functionality. The more important is to find out how the decryption is happening and then you can decipher any code snippets. From this point, you can try yourself to decrypt every chunk of data and find out how they are being used for every malicious impact.

Extracting C&C Configuration

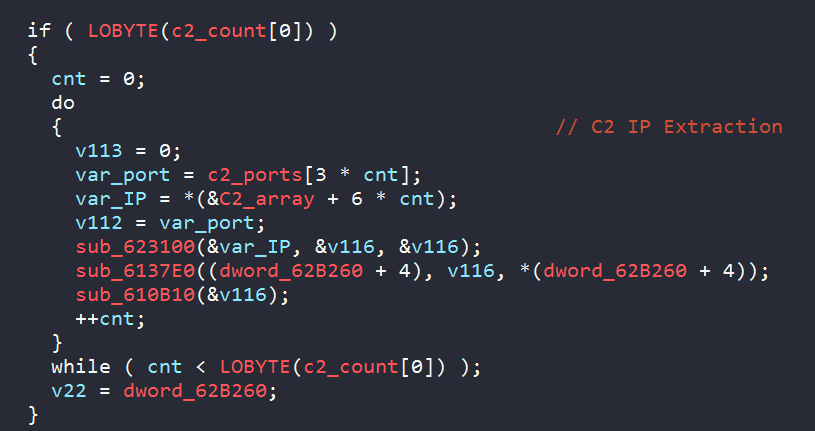

Dridex of course tries to connect with its threat actor. It’s a must to find these remote ends in order to block them and cut out the lines between the malware operators and the infected machines. One way to find out the C&C servers, is to look for where networking functions are being called. From Xrefs to mw_API_Resolver, we can find that there are two important functions which are responsible for networking functionality; sub_623370 and sub_623820. At sub_623820, it seems that it is used for further download activity, because it’s resolving the InternetReadFile API. Inside sub_623370, we can see Dridex is resolving InternetConnectW API which accepts the lpszServerName parameter. This parameter identifies the remote end to where the connection is happening.

Tracing the only Xref to sub_623370, we can spot Dridex parsing a data offset to extract the embedded IPs. This is at the address 0X5F7232 just a little before the call to sub_623370.

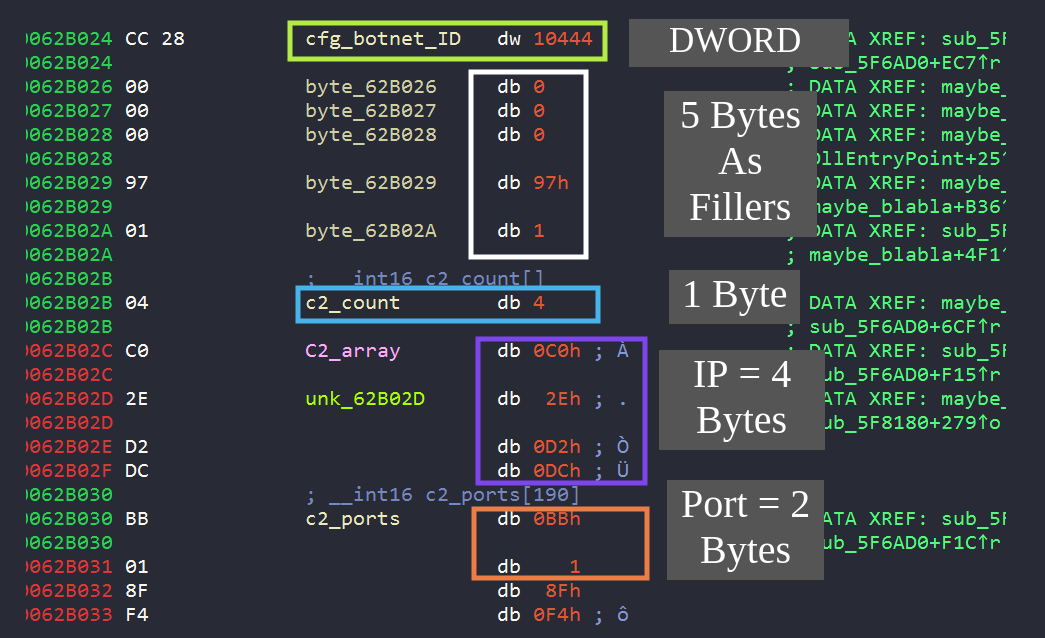

The network configuration is not encrypted. Starting at offset 0X62B024. The ports can be converted via simple hex to decimal conversion. Yet, for the IPs we can use this small Python script to convert them into a human-readable format:

import socket

import struct

def int2ip(addr):

return socket.inet_ntoa(struct.pack("!I", addr))

print(int2ip(0xC02ED2DC)) # First IP

The extracted C&C IPs are below:

| No | IP Address : Port Number |

|---|---|

| 1 | 192.46.210.220:443 |

| 2 | 143.244.140.214:808 |

| 3 | 45.77.0.96:6891 |

| 4 | 185.56.219.47:8116 |

Conclusion

The techniques of Dridex are somehow unique when combined together. We can easily defeat API hashing once we know the hashing algorithm and the XOR key. The use of VEH makes the reverse engineering process very painful and needs urgent patching. Dridex has a lot of capabilities and techniques, I’ve decided to rather focus on defeating anti-analysis and strings decryption. From there, you are able to identify any of its intentions.

IoCs

| No | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unpacked Sample Hash | F9495E968F9A1610C0CF9383053E5B5696ECC85CA3CA2A338C24C7204CC93881 |

| 2 | 1st C2 | 192.46.210.220:443 |

| 3 | 2nd C2 | 143.244.140.214:808 |

| 4 | 3rd C2 | 45.77.0.96:6891 |

| 5 | 4th C2 | 185.56.219.47:8116 |

| 6 | Botnet ID | 10444 |